Toppola is one of those Scandinavian inventions that seemed too bold to survive – but somehow did, long enough to carve out its own subculture inside the Saab community. The idea was strange even by the imaginative standards of the 1970s and 1980s automotive world: instead of building a camper van, what if you transformed a Saab into a camper by replacing the rear hatch with a molded composite module containing a bed, storage space, and enough room to stand upright?

The result looked part spacecraft, part ski lodge, part curiosity. But for those who used one, it became something else entirely: a way to turn a Saab into a rolling sanctuary, a car that could swallow the open road and provide shelter at the end of it – without sacrificing the brand’s unmistakable driving character.

Toppola was never meant to be mainstream, and it never tried to be. Yet its story stretches across two countries, several generations of Saabs, and decades of owner devotion. And today, as surviving modules circulate through Swedish, Finnish, and Norwegian classifieds, the legend only grows stronger.

How a Finnish Sketch Became a Swedish Icon

Every version of the Toppola story begins the same way – with Arwo Pullola, a Finnish visionary who believed that a family car could be more than its sheet metal suggested. In 1980, he chose the Saab 99 as his base. The 99 was everywhere in Finland, rugged enough for northern roads, and offered in both three- and five-door formats—ideal candidates for a removable camping module.

Pullola drafted the concept, shaped its proportions, and validated the idea. Accounts vary on how many prototypes he actually built, but the blueprint was unmistakable: remove the rear hatch, bolt in a lightweight composite structure, and create a micro living space sitting atop Sweden’s most resilient family car.

His work caught the eye of two Swedish craftsmen – Matts Molestam and Peter Malmberg – with deep experience in boat interiors and small-craft cabinetry. They purchased Pullola’s rights in 1982 and built a module that was no longer just a sketch, but a finished product with details, structure, and a shape that would later become unmistakable.

The company they formed, Emico AB, had inadvertently created a new kind of Scandinavian mobility: one that stretched Saab’s utility far beyond traditional boundaries.

Why the Saab 99 and 900 Became the Natural Home of the Toppola

From the start, the Toppola wasn’t a universal solution. It needed a specific kind of car – one with the structural durability, hatch opening geometry, and suspension robustness to cope with additional height and load. Saab’s hatchbacks were uniquely suited for this, particularly the 99 Combicoupé and later the 900.

The Saab 99 offered a long rear overhang, a rigid floor, and a dependable two-liter engine with either 108 hp (NA) or 147 hp (turbocharged). It didn’t mind the extra frontal drag or the weight shifting over its rear axle. The car simply absorbed it and kept driving, often over thousands of kilometers of Norwegian fjell passes or remote northern roads where campsites were few and the outdoors demanded creativity.

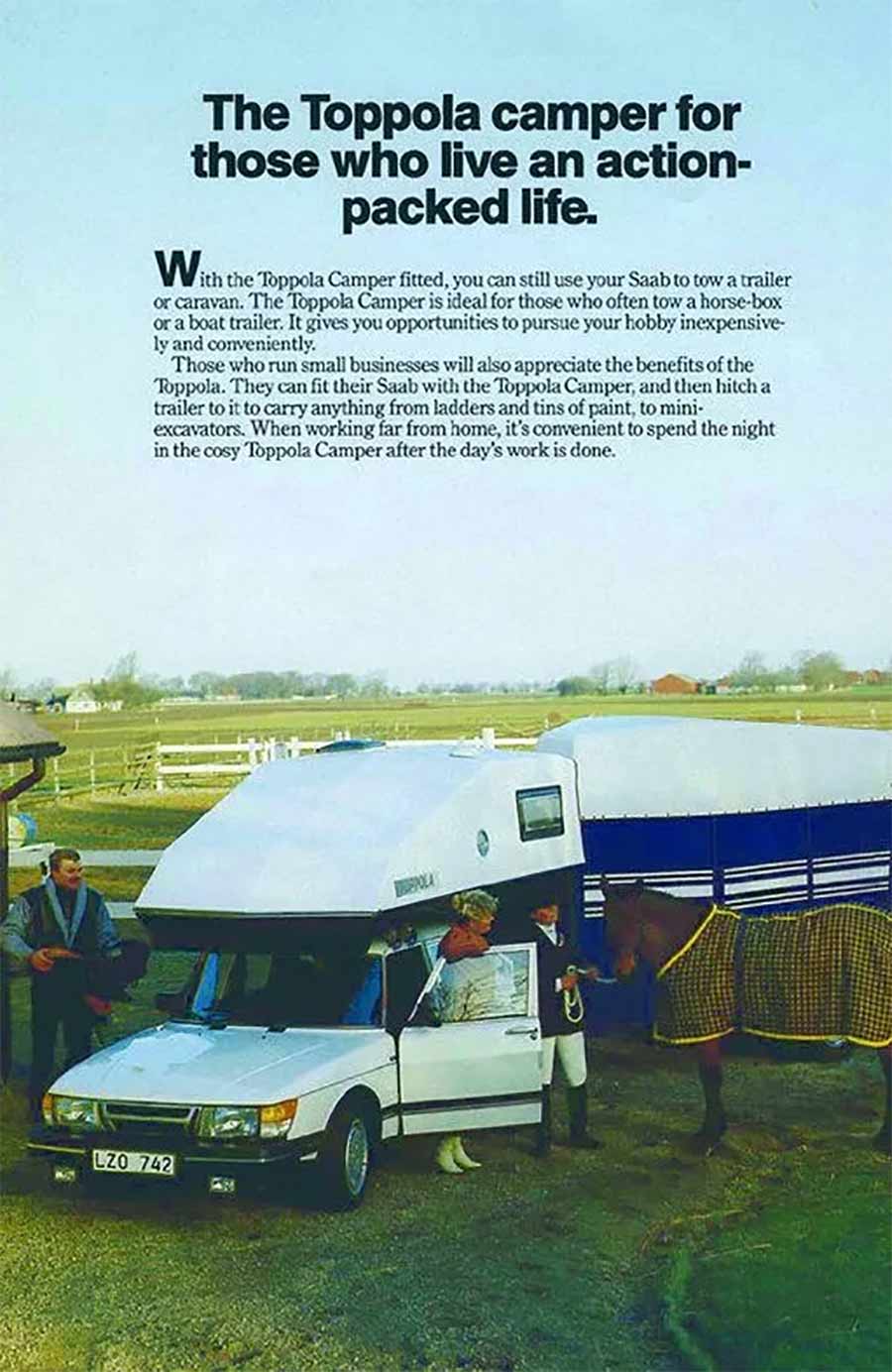

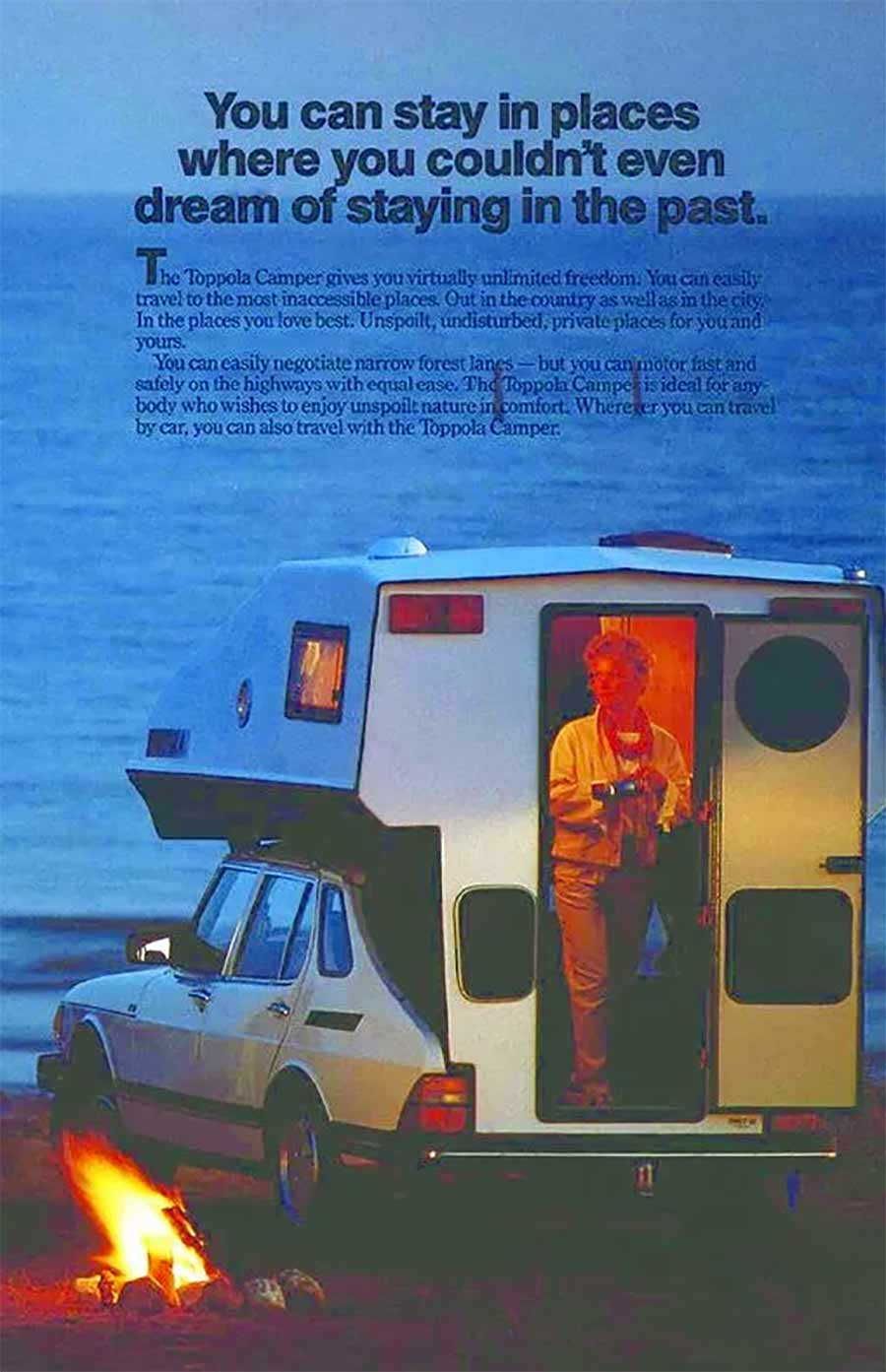

The Toppola module itself was surprisingly comfortable. The sleeping platform extended over the car’s roof, creating a 170 × 200 cm bed, while the living area dropped into the luggage compartment. If you weren’t too tall, you could stand comfortably in the lower section. A clever ecosystem of accessories evolved—curtains, storage compartments, even a tent-shaped vestibule that attached at the rear.

For many Saab owners, especially in the early 1990s, this wasn’t a novelty. It was liberation. You could leave Stockholm on a Friday afternoon, drive until the road felt right, and sleep wherever the forest met the sky.

And for today’s readers curious how such Toppola-equipped Saabs actually behave in the wild, one of the best preserved period examples remains the 1992 Saab 900S Toppola we featured here on SaabPlanet – its owner using it exactly as the concept intended, far from the constraints of ordinary camping.

The Saab Factory’s Brief But Fascinating Interest

Saab noticed what was happening. Dealers in Scandinavia began receiving inquiries. Customers were showing up with photos. Some were even asking whether Toppola could be ordered new through official channels.

The company listened.

By 1984, Saab commissioned Emico AB (Emico West) to develop Toppola modules designed specifically for the newly launched Saab 9000. This was not a half-hearted gesture; engineers consulted with Emico on styling alignment and proportions, ensuring the Toppola looked like a natural extension of the car rather than an aftermarket oddity.

But the partnership did not survive long. According to reporting from the period, Saab pushed aggressively for higher production capacity and shorter lead times. Meanwhile, Emico realized it may have embraced more demand than it could actually fulfill. By the mid-1980s, tensions reached a point where cooperation ended abruptly.

Yet that single moment – Saab officially endorsing the concept – cemented the Toppola in the brand’s cultural memory forever. It wasn’t just a quirky accessory anymore. It was something Saab itself had seriously considered.

When the 9000 Became a Camper: Enthusiasts Finish What the Factory Started

Although the factory collaboration ended, the idea did not.

If anything, the Saab community took it as an invitation.

One of the most remarkable examples is the TGB9000 Super Toppola, perhaps the most ambitious Saab camper conversion ever completed by an enthusiast. It proved that the 9000—roomy, structurally robust, and engineered for long-distance touring—was arguably a better platform than the classic 900.

Then came Robert Solstad’s Saab 9000 camper, a project that rewrote what a “DIY vision” could mean. Solstad didn’t simply mount a Toppola; he engineered a bespoke module with a distinct silhouette, turning the executive hatchback into a Scandinavian micro-motorhome that still retained the driving characteristics of the car underneath.

These builds underscore a simple truth: while the Toppola was born for the 99 and matured on the 900, it found its most refined expressions on the 9000, a model whose chassis, powertrains, and long-distance character aligned perfectly with the spirit of the concept.

Today, these 9000-based conversions are exceptionally rare. They exist as symbols of what might have happened had Saab and Emico found a sustainable production rhythm in 1984. And they serve as a reminder that Saab owners have always been a step ahead when imagination meets engineering.

A Short-Lived Revival and the Final Attempts to Industrialize the Concept

After Emico’s withdrawal, rights to the Toppola transferred in 1986 to a firm called Scando, which attempted to globalize the idea. But Saab alone could not support the volume needed to justify industrial expansion; Scando wanted Toppola modules to fit mass-market cars like the Ford Scorpio, Sierra, Citroën hatchbacks, and even Japanese imports.

Despite a decade of effort, the math never worked. Production ended in 1996 after only about 300 units were built across all generations. Rental fleets absorbed a portion of the output, introducing European customers to a style of travel they didn’t know existed. But the dream of widespread adoption faded as quickly as it had appeared.

Even so, the shape, proportions, and aura of the Toppola became so iconic that later enthusiasts created tributes – including the Saab 900 Toppola scale model kit, which today serves as a miniature memorial to a chapter of Saab culture that refuses to disappear.

And in Hungary, one builder even produced a Toppola replica for a classic 900, proving the design still inspires creativity nearly forty years after its debut.

How Toppola Lives On: A Community That Refuses to Let an Idea Die

You can tell a lot about a brand by the things its community refuses to let go of. And in the case of Saab, Toppola ranks alongside the Viggen wing, the Talladega run, the 900 Turbo’s APC evolution, and the entire heritage of rallying in winter forests.

A Toppola is not just a camping module. It’s an attitude.

It’s a decision to take the road that doesn’t appear in guidebooks. It’s a belief that a car doesn’t have to be large to take you far. And it’s a reminder that Saab owners have always found ways to use their cars differently from everyone else.

That spirit is perfectly captured in the first episode of “Saab Life Stories” – a tale about how a single decision can reroute a life. The Toppola fits that same emotional arc: a small thing that changes everything.

Even now, Toppola-equipped Saabs surface occasionally in Swedish and Norwegian classifieds, often priced between $5,000 and $15,000 (or local equivalents), depending on condition and whether a car is included. Surviving examples are few, but demand is surprisingly strong. Some buyers just want the novelty. But others—those who understand what Saab was and what it could do – want the experience.

Why the Toppola Still Matters Today

We live in a time when modern mobility pushes drivers toward regulated, sanitized, algorithmically optimized experiences. The roads are watched, the cars are connected, and spontaneity is often discouraged by design.

Yet the Toppola persists as a quiet counterargument.

It reminds us that freedom once meant removing the hatch of your Saab 900, bolting on a shell molded in a Swedish workshop, and driving into the night with nothing but your headlights and a remote lay-by to call home. It is an artifact from the era before mobility needed permission.

Most importantly, the Toppola reflects the essence of Saab: resourceful engineering meeting real-world imagination. Few car brands could host such a concept without descending into parody. Saab made it look natural.

And that is why, decades later, the Toppola still resonates—not as a curiosity, but as a cultural extension of a brand that encouraged drivers to rethink what mobility could be. And for those who wish to dive even deeper into the history, variations, and surviving examples of this unique camper concept, the dedicated archive curated by Ego Ákos, president of the Saab 900 Club Hungary, offers an exceptional resource at toppola.hu.

I bought a 900 in Sweden that carried a toppola. The guy had two. I thought a could buy one for a 1000 eu. Lol. No chance. He said they worth about 5000 eu each. I only payed 500 eu for the car. Lol..worth more now. This was three years ago. There was a Polish company making a replica also. Don’t know the name. I’ve wanted one for 40 years. From my first 900.

I think embraced by saab owners realising ..how many that have survived.

Maybe an idea for A convertible that has a top thats shot.

im looking for info about Routel imperial hom

its almost giving me an idea to scratch build one for my 900

Video of this vehicle:

https://youtu.be/HYKajD82TGA?si=oFxUpQICdrap_cfr

Se em Portugal fosse fácil de legalizar eu fazia um