A forgotten Saab face in an Italian aircraft museum

Walk through Volandia, the aviation museum next to Milan-Malpensa, and you expect winged shapes, roaring turbines and the usual timeline of Italian aeronautical pride. What you do not expect is an orange, low-slung Saab-based concept car sitting quietly among the aircraft, wearing a small plaque that simply says “Saab Novanta – Bertone Saab”. Next to the car, that plaque lists numbers Saab fans usually never see associated with this prototype: 2,790 cc, 6-cylinder V, 255 CV, built in 2002.

For most Saab enthusiasts, the Novanta has always been an elusive presence in press photos and old tech articles – a silver show car, somewhere between Turin and Paris, built for Michelin’s Challenge Bibendum and quickly disappearing into the fog after Bertone’s bankruptcy. Now we know where it landed: inside the ASI Bertone Collection, preserved as Italian industrial heritage and on public display at Volandia.

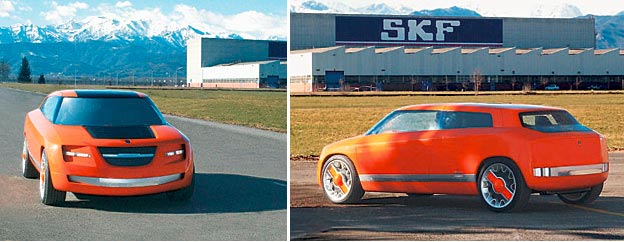

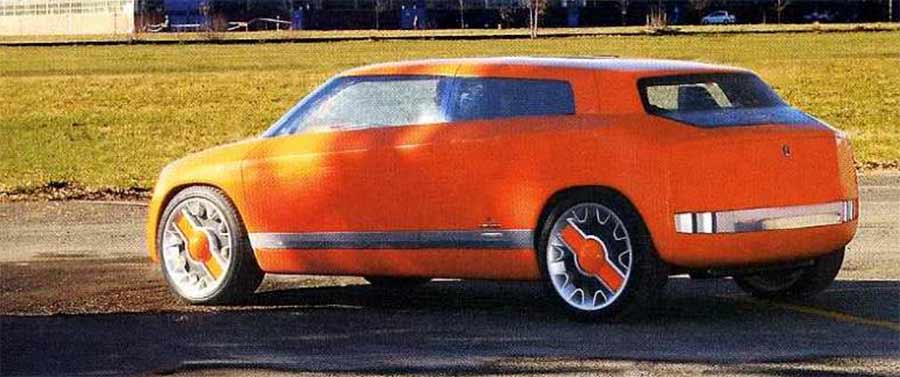

Seen in person, the car instantly feels more Saab than many expected. The roof “canopy” floats above darkened A-pillars, the front carries a wide grille with a familiar shield and Griffin, and the stance suggests a muscular 9-5 that has been smoothed and stretched by an Italian stylist’s hand. Yet Novanta is not just a design exercise. Underneath the skin – and in the story that brought it to this museum – sits one of the most radical technological experiments ever mounted on a Saab platform.

This is the long, unusual journey of Saab Novanta, from birthday present and rolling joystick experiment to locked-in museum piece that cannot legally leave Italy.

A birthday present with Swedish bones and Italian tailoring

The name explains the original intent. “Novanta” means ninety in Italian, and the car was conceived to celebrate 90 years of Carrozzeria Bertone. Rather than build yet another static sculpture, Bertone partnered with SKF, the Swedish specialist best known for bearings and seals, to create a fully drivable concept that would showcase the supplier’s most advanced drive-by-wire hardware.

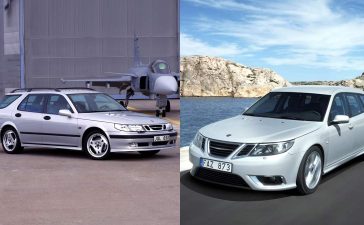

For the mechanical base, Bertone and SKF chose something solid, safe and recognizably Scandinavian: the Saab 9-5. SKF’s own technical literature describes the Novanta as being built on a 9-5 three-liter V6 platform, with Saab drivetrain components providing the dependable Swedish backbone. Saab got a sudden, unexpected presence in one of the most forward-looking technology showcases of the early 2000s.

The timeline is tight but clear. The Novanta debuted at the Geneva Motor Show in March 2002, only a year after Bertone and SKF had first tested their earlier Filo concept. Later that year, the car was entered in the Michelin Challenge Bibendum 2002, a rolling laboratory and public event for clean and advanced vehicles, held in Germany and France and culminating at the Paris Motor Show. There, the Novanta picked up the award for “Best Prototype Car” for its innovative use of drive-by-wire technology.

From a Saab perspective, the most interesting detail is how naturally the Swedish brand’s design DNA blended with Italian show-car thinking. In photographs and in Volandia’s soft museum light, the Novanta looks like a relative of the Saab 9X concept (2001) and, a few years down the line, the 9X BioHybrid and 9-4X concept. The black-edged roof, the thick C-pillars, the continuous light bands in the front and rear – all of these would later reappear in Saab’s own design work. Bertone helped Saab build the physical 9X show car, and those influences clearly ran both ways.

According to the Italian museum plaque, the Novanta is officially catalogued as:

- Brand: Bertone Saab

- Model: Novanta

- Year of construction: 2002

- Engine: 6-cylinder V, 2,790 cc

- Power: 255 CV

That data sits somewhat at odds with SKF’s original figure of 3.0-liter displacement and 200 bhp, but we will return to that discrepancy later. What matters in historical terms is that the Novanta wore Saab mechanicals and Bertone’s 90th-anniversary suit, while SKF used it as a full-scale demonstrator of where vehicle control might be heading.

When Saab’s aviation DNA went fully electronic

For Saab people, the phrase “drive-by-wire” immediately triggers aviation associations. Saab’s roots in aircraft manufacturing made the step from fly-by-wire to drive-by-wire more than a marketing slogan. The brand had already experimented with the idea on an experimental Saab 9000 in 1992, a car where traditional mechanical linkages were replaced with electronic signals for steering and braking.

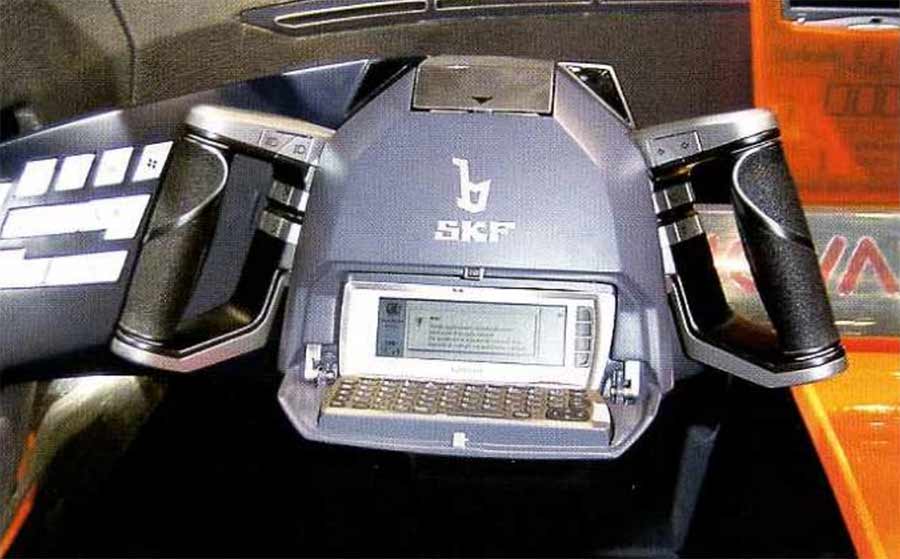

Novanta took that thinking and let SKF push it several stages further. The concept dispensed with the classic steering wheel, brake pedal and accelerator entirely. In their place sat an angular, twin-yoke controller called “Guida” – a human-machine interface that looked part aircraft sidestick, part motorcycle handlebar.

The idea was simple to describe and complex to execute:

- Rotate the yokes to steer.

- Twist or pull to control power.

- Squeeze to brake.

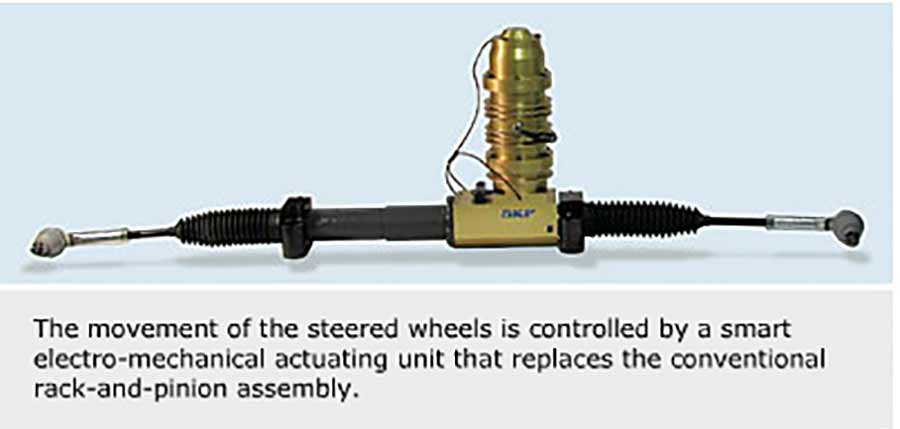

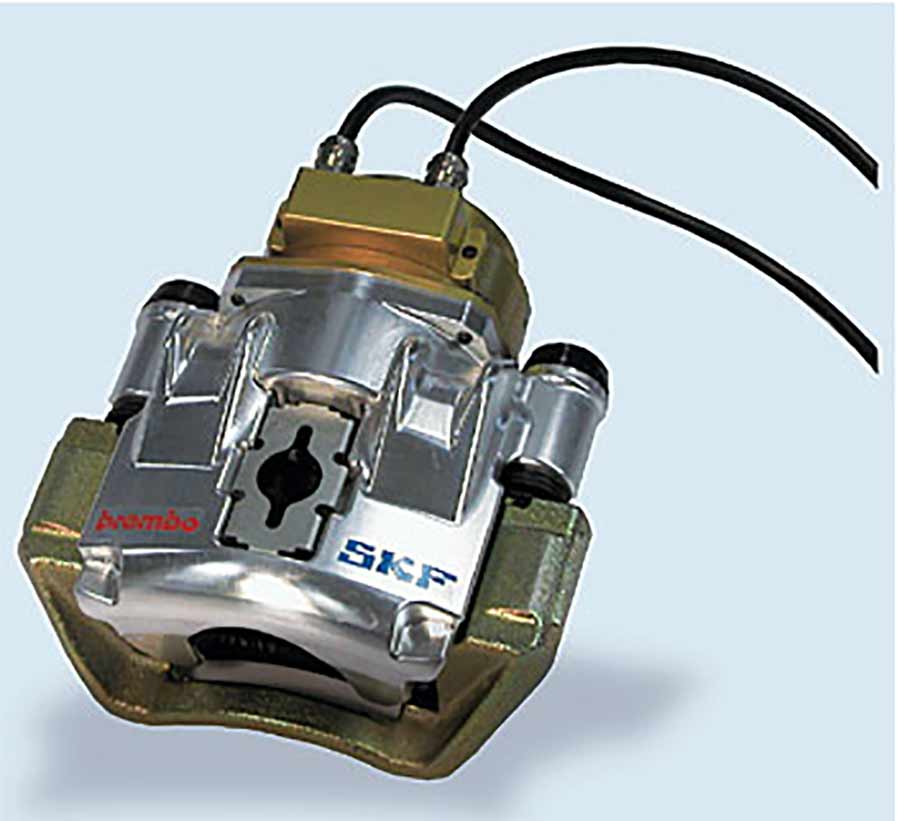

Every movement was captured by position and load sensors inside the Guida. Those sensors sent signals along a fault-tolerant communication network to so-called smart electro-mechanical actuating units (SEMAUs). There, electric motors and integrated controllers converted the digital orders into motion: turning the front wheels, applying the Brembo brake calipers, or commanding gear changes in the automatic transmission.

Because the system was fully electronic, engineers could tune steering response by speed – quick and eager at city pace, calmer and more stable on the motorway – without changing any physical hardware. SKF’s documentation talks about improved steering feel over the earlier Filo, better braking consistency, and a sophisticated recovery strategy: in the event of a failure, the system would instantly switch to backup modes to keep the car controllable.

Inside, everything was built around this new interface. There was no visible steering column, freeing up space, improving crash safety and giving the cabin a light, lounge-like atmosphere. A fingerprint scanner on the dashboard acted as both key and personal profile selector, recalling Saab’s traditional focus on ergonomics and driver-oriented cabins, but executed in a completely new way. Linked features included driving-position memory, climate settings, service reminders and even audio preferences stored per driver.

It was an extremely early sketch of what we today call a connected, profile-based cockpit. Saab owners familiar with the way their cars remember seat and mirror positions via the key fob will recognize the logic – Novanta merely extends it and strips away the mechanical parts.

That is why Novanta matters for Saab history: it shows that Saab hardware and Saab design were already being used to explore the kind of interfaces that modern EVs and autonomous prototypes now consider standard.

A Saab that looked forward while wearing familiar shapes

Technically radical does not mean visually alien, and this is where Bertone’s hand becomes obvious. The Italian description on the Volandia plaque calls attention to the “pulizia formale” – the formal cleanliness – of the exterior. The doors have no visible handles, the surfaces are uninterrupted, and the lighting is reduced to sharp, luminous blades. All of this was meant to make the architecture appear minimalist, while actually using subtle reflections and light play on the panel edges to give the car visual balance and tension.

Look at the Novanta from the front and the Saab link is immediate. There is a broad central grille flanked by two narrow air intakes, with the Griffin badge placed prominently on the leading edge of the hood. The headlamps form horizontal light bands that look very much like early LED strips, years before that became common in production cars. That same graphic would later appear refined and production-ready on the second-generation Saab 9-5 and the Saab 9-4X, with their so-called “ice-block” light signatures.

From the side, the roof appears to float above a continuous glass band, supported by dark A-pillars and a thick rear pillar. This “canopy” look turned up again on the 9X BioHybrid concept and then, in more restrained form, on the 9-5NG. Saab fans often think of those later cars as the brand’s boldest design steps; Novanta demonstrates that some of those ideas were being modelled and tested years earlier on a joint Saab-Bertone project.

One unusual detail that tends to be mentioned only in passing is the door layout. On the driver’s side, Novanta has a single long door; on the passenger side it carries two shorter doors, and the whole structure is B-pillarless. It is an asymmetric solution designed to combine coupé-like access for the driver with more convenient rear entry on the sidewalk side – a concept that never reached production but shows how far Bertone was willing to rethink the executive sedan template.

Even the wheels were ahead of their time. SKF’s technical data references 20-inch alloys with 245/40 tires, huge by early-2000s standards on a road-oriented sedan. Combined with the low, stretched profile and the Saab-like nose, the car still looks surprisingly contemporary on the museum floor. Many visitors walk past, assume it is a 2010s electric prototype, and only stop when they read the construction year: 2002.

What was really under the skin? The numbers don’t fully agree

Saab people are used to caring about the details: displacement codes, engine stamps, gearbox variants. With Novanta, those instincts run into the messy reality of concept-car life.

SKF’s original technical documents, prepared for the Michelin Challenge Bibendum and for engineering publications, consistently describe the car as using a 3.0-liter V6, 24-valve engine producing 147 kW (200 bhp) at 5,000 rpm, with 310 Nm of torque at 2,200 rpm. In other words, the familiar B308-based Saab 9-5 V6 – not tuned for maximum power, but perfectly adequate to move the additional electronics and demonstrate the drive-by-wire systems.

The Volandia plaque, however, lists a 2,790 cc displacement and 255 CV. That combination does not match any known production Saab V6. It may be a typographical error, a rounded figure based on some internal Bertone document, or simply a generic “V6 around 2.8 liters with roughly 250 hp” entry created when the collection was catalogued. Another possibility is that the museum chose to harmonize figures with later GM-Saab 2.8-liter turbo V6 specifications, which hovered around 250-280 hp, even though that engine did not exist in 2002.

Concept cars often live in this grey zone. They start on one mechanical base, then are modified, partially disassembled, or even immobilized when their primary job is done. Over time, documentation gets rewritten for public display, sometimes more in line with marketing expectations than with engineering reality.

For Saab historians, the safest stance is to treat the Novanta as what the SKF engineering texts explicitly say it is:

- a Saab 9-5 V6 platform,

- carrying a three-liter, 24-valve V6 around 200 hp,

- used as a rolling laboratory to validate steering-by-wire, brake-by-wire and throttle-by-wire systems.

The museum plaque then becomes an interesting artefact in itself – evidence of how quickly our collective memory smooths over the uncomfortable details and replaces them with round numbers.

From bankruptcy files to a protected piece of Italian heritage

After the Michelin Challenge, some press drives and a few technology demonstrations (including one in Michigan in 2005 near SKF’s North American technical center), the Novanta quietly disappeared from public view. When Bertone’s finances collapsed and the legendary design house entered bankruptcy, its in-house museum and concept collection suddenly became vulnerable.

In September 2015, the liquidator organized an auction of 79 prototypes and significant vehicles from the Bertone collection. The Saab Novanta appeared on the list with a surprisingly modest starting price of €22,000, grouped together with icons like the Lamborghini Miura and Countach, Lancia Stratos, Alfa Romeo Montreals and various radical show cars.

Here the story takes a decisive turn. Instead of being split up and scattered among private collectors worldwide, the entire collection was acquired by ASI – Automotoclub Storico Italiano, the Italian historic vehicle association. The Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage classified the Bertone collection as cultural property, explicitly forbidding the breakup of the set and its export abroad.

That legal move has two consequences. First, it saved the cars, including the Novanta, from being sold off piecemeal. Second, it effectively locked them into Italy for good. The Saab Novanta, despite its Saab mechanicals and Swedish input, is now legally part of Italian cultural heritage.

Today, the ASI Bertone collection is displayed at Volandia – Parco e Museo del Volo, near Milan-Malpensa airport. Walking through the halls, visitors encounter a compressed history of post-war Italian coachbuilding, from the Alfa and Lancia show cars to wedge-era Lamborghinis. In that context, the Novanta plays a double role:

- As a Bertone project, it showcases how the design house engaged with electronic control systems and new interior architectures.

- As a Saab-based platform, it quietly represents Sweden in a room otherwise dominated by Italian badges.

For Saab fans, there is a bittersweet undertone. The only complete Novanta ever built is safe, maintained and visible to the public – but it will almost certainly never leave Italy again, not even for a Saab festival in Trollhättan. If you want to see this particular chapter of Saab history in person, you have to make your way to a former aircraft factory just outside Milan.

How Novanta fits into Saab’s wider experiment with the future

Seen from 2025, Novanta feels less like a wild detour and more like a missing piece in Saab’s long experiment with future-oriented technology. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, the brand flirted with ideas that only now are reaching mainstream production:

- Drive-by-wire steering and brakes in the 9000 prototype and later in Novanta.

- Bi-fuel, hybrid and bio-ethanol drivetrains, explored in concepts like the 9-3 BioPower Hybrid and 9X BioHybrid.

- Advanced active safety and cockpit ergonomics, from Night Panel to SAHR head restraints and sophisticated crash structures.

Novanta sits at the intersection of several of these threads. The car itself never wore a Saab badge on a showroom floor, but the Saab platform gave credibility to SKF’s by-wire story and provided a familiar shape for a very unfamiliar control scheme. Bertone’s design, meanwhile, established visual motifs that Saab’s own design teams would refine in later concepts and production cars.

The irony is that drive-by-wire did not arrive in the dramatic form Novanta suggested. We still use steering wheels, and most drivers would react badly to joystick-only controls in a family sedan. Instead, by-wire systems quietly filtered in through less visible channels:

- Electronic throttle control is now standard on virtually every car.

- Electric power steering has replaced hydraulic pumps and belts.

- Electronic parking brakes have eliminated handbrake levers and cables.

In other words, many Saab owners today already live with partial drive-by-wire systems without thinking about it. The fully de-mechanized vision of Novanta has been superseded by an even bigger cultural shift: autonomous driving and driver-assist systems, where the human is gradually removed from the loop altogether.

Seen in that light, Novanta is both prophetic and slightly naive. It assumes a future in which the driver remains central but interacts with the machine through a radically different interface. Two decades later, the industry is leaning toward a future where the driver might not be needed at all. Yet the questions Novanta asked – How much mechanical connection do we really need? Where can electronics improve safety and design freedom? – are the same ones being answered today in EV start-up studios and traditional OEM R&D centers.

Why Saab enthusiasts should care about an orange concept in Volandia

For the Saab community, Novanta offers several reasons to pay attention.

First, it proves once again that Saab punched far above its weight as a technology partner. SKF could have wrapped its drive-by-wire hardware in any anonymous mule. Instead, it chose a Saab platform, then partnered with one of Italy’s great design houses to clothe it in a body that visibly references Saab’s contemporary and future design language. That tells you something about the brand’s reputation inside the engineering world at the time.

Second, Novanta demonstrates that Saab’s design DNA travels well. Even when Italian stylists re-imagine the car from scratch, they keep the recognisable front graphic, the clean surfacing and the cockpit-like cabin priorities. For fans of the 9-5NG and 9-4X, Novanta is an ancestor worth revisiting.

Third, the car’s current situation – preserved inside an aviation museum, part of a legally protected design collection – resonates with the wider Saab story. Both the brand and this particular prototype have left the commercial arena and entered the world of heritage and memory. They survive thanks to enthusiasts, institutions and a shared refusal to let interesting ideas fade away quietly.

Finally, the small factual inconsistencies around the car – the conflicting engine data, the nearly forgotten drive events, the confusion over whether it celebrated Bertone’s birthday or SKF’s technology (in truth, both) – are typical of concept-car history. They remind us that documenting Saab’s past is a living process. Each museum visit, each recovered spec sheet or photograph, adds detail and corrects old assumptions.

Prototype built as a unique example on a Saab platform and mechanics. The major novelty inside is the drive-by-wire system that uses a console similar to a PlayStation. Outside, the new luminous blades of the lights and the handle-less doors maximize the formal cleanliness of an apparently minimalist architectural composition, which in reality is very carefully designed to use light reflections on the sharp edges of the sheet metal to balance the volumes.

In that short paragraph, you have the whole spirit of Novanta. Saab hardware. Radical control systems. Minimalist-looking design hiding a lot of thought. And the understanding that cars can be cultural objects, not just transport.

For a brand that built its identity on aircraft thinking, safety obsession and a stubborn streak of originality, there are worse fates than being remembered through an orange concept car in an aeronautical museum. The Novanta might never have worn a production badge, but it still carries Saab’s story – in silicon, in sheet metal and now, permanently, in Italian cultural archives.