How This Piece Came Together – From an Italian Teardown to a Lived-memory Audit

Before we dive into the period context, here’s why we’re talking about the Saab 900 Turbo today. The spark is Real Car’s video, “The Whole Truth About the Saab 900 Turbo,” hosted by Fabrizio Jannetta and Gabriele Brunetti – a channel with 70k+ subscribers and a distinctly Italian way of mixing technical detail with irreverent asides. Italy isn’t a random backdrop here: it’s a country where design language, brand codes, and motorway reality shaped how the 900 was bought, driven, and remembered.

For this article we worked directly off the episode (see embed below) and the long Italian comment thread beneath it. We pulled out the time-stamped technical claims (APC logic, “backwards” powertrain layout, aero add-ons that actually manage pressure) and then cross-checked them against owner recollections: what the cars did on italian A4 and A14 in the ’80s and ’90s, what really failed, what never did, and how cockpit ergonomics translated into lower fatigue at 160–180 km/h. Where numbers in the video vary by model year or trim (for example, quoted Cd figures and brake specs), we keep the principle and flag the variance rather than pretending there was only one “900.”

The result isn’t a recap of jokes; it’s a two-source narrative – the hosts’ engineering walk-around plus the street-level institutional memory of Italian owners and mechanics. That combination corrects the modern meme that the 900 was “misunderstood” or merely “odd.” With that provenance set, we can now talk about what the car meant when it was new—and why those choices still read as rational in 2025.

Not “Misunderstood”: In Mid-’80s Italy It Was Aspirational, Not Esoteric

If you only meet the Saab 900 Turbo through modern memes, you miss how it actually landed on the street in the mid-1980s – especially in Italy. Contemporary owners recall the coupé, five-door, and, from 1987, the convertible as status markers for a specific professional set: managers, architects, ad people, designers, footballers, and ambitious sales reps who didn’t want the default German sedan. Several italian commenters frame it simply: Volvo was another icon, Mercedes was for the rich kid, and the Saab 900 Turbo was for people with their own taste. The sticking point, they say, wasn’t rejection; it was price and early turbo niggles. That tracks with period reality: the 900 Turbo’s list price and options pushed it against better-known badges while its equipment and engineering made it feel special in day-to-day use.

Owners underline that aesthetics must be judged in period. In the 1980s, angular sedans like Volvo 740/760 were read as sculptural rather than crude, and the 900’s proportions—long hood, raked glass, fastback tail—fit the era’s emphasis on aerodynamic efficiency and visual purpose. The open contempt some modern viewers show for the 900’s looks was not the consensus then, and Italian street memory supports that. One reader even jokes that showing up to a date in a 900 Turbo “helped your odds,” because presence plus comfort made an impression. That social context matters: cars signaled identity, and the Saab signal was competence over flash. Even today, commenters frame the 900 as a thinking person’s express, a car that made you arrive less tired and got better the longer you stayed with it.

These recollections add an important corrective to the video’s running gag that the 900 is “ugly.” The design is intentional: much of what looks odd is airflow and packaging, not failed styling. In period, that purpose read as modernity, not contrarianism for its own sake.

What Real Car Gets Right: Packaging Logic, APC, and the Structure That Justifies the Mass

Fabrizio Jannetta’s walk-around hits the engineering notes that Saab people expect. The “cofango” (hood wrapping into the fenders) is there for rigidity and access. The front bumper depth reflects US crash rules and cooling real estate once intercooling and Turbo plumbing arrived. The curved windshield and the self-cleaning rear screen speak to pressure management as part of the form. The Cd figures cited in the video vary by trim and kit, but the principle is correct: every add-on manages flow, lift, or temperature. The flat-nose fascia, splitter, ducting, and spoilers are not décor; they are aero tools.

Under the hood, Real Car’s “backwards” lesson is the one you show non-Saab friends: longitudinal inline-four canted ~45°, gearbox slung below, chains in the head, clutch accessed from the front without yanking the entire drivetrain. That weirdness is service access by design. Heat management compromises exist – the battery’s proximity to turbo hardware drew justified criticism – but the heat shield and routing are part of a coherent package, and owners who keep those parts healthy see the difference.

The APC (Automatic Performance Control) section is on point. Saab’s move to modulate boost via the wastegate in response to knock sensing, rather than just cutting ignition advance, preserved torque and drivability across 92–98 RON realities. Water-injection kits existed in period, and they did what the video says: pull temps down and keep combustion stable under sustained load. It’s not folklore; it’s how Saab reconciled turbo performance with daily abuse long before “ECU tuning” was a consumer phrase.

On structure, Real Car’s “~40% more robust” claim against contemporaries matches owners’ lived experience: heavier doors, high torsional feel, triple-joint steering column, multi-density bumper structures, and programmed deformation all point to passive safety as a core brief. That’s why period testers wrote about high-speed stability and why Italian commenters reminisce about insane motorway averages before Tutor enforcement: the car sits, steers, and brakes with surplus on rough, fast roads.

Cockpit Genius: Why Italians Still Call the Driver’s Seat “Assurda”

Several comments single out the driving position as “assurda” in the best way. The seat base, backrest contour, head restraint, and control clustering were engineered for long-distance clarity. The key in the console remains a talking point. The video frames it as safety in a frontal hit; an owner counters with anti-theft logic, noting the reverse-to-remove interlock and how the lever base would shear if forced before the lock. Both readings are part of Saab’s logic web: occupant safety, anti-tamper behavior, and human-factor discipline in one move.

Italian owners also highlight quiet, effective HVAC, with the caveat that in warm climates AC runs almost year-round. One commenter insists you could hear the blower only at max and that the airflow strategy (vents, demist logic, duct sizing) suited long days. Another remembers double-curvature glass and A-pillars oriented to reduce obstructions. Whether or not each memory is textbook-precise, the pattern is clear: visibility, body-motion control, and seating combine to make the 900 fatigue-resistant. You arrive feeling like a professional who still has a second half to play.

Performance Reality: Turbo Lag, Cruise Speeds, and What Consumption Actually Looked Like

The comments split on consumption. One calls the “10 km/l” (≈ 23.5 mpg US) optimistic at 200 km/h cruising; another says consumption was competitive for the time, citing 11–12 km/l under sane conditions. Both can be true. The 900 Turbo will drink if you sit deep in boost at 180–200 km/h for hours (Italy in the ‘80s allowed that to happen); it will also return sensible numbers when you drive with APC-blended torque and early upshifts. That’s the point of Saab’s knock-aware boost: usable thrust without detonation, not brochure heroics.

On turbo behavior, “poco turbo lag” comes up more than once. Period Garrett units are not modern ball-bearing snails, but APC and gearing give you mid-range shove that matters on real roads. Call it the “calcio del mulo” the commenter mentions: in the middle of a bend, on a grade, the torque arrives in a way you can place. That’s why owners recall mix-road superiority versus contemporary power heroes that felt sleepy off-boost. It also explains the folk wisdom: idle the engine 30 seconds before shutdown to let oil cool through the turbo center section—good practice then, sensible now.

Brakes, Axles, and the Stuff You Discover Only After 150,000 km

Several Italian voices dive into parts variances you never see in brochure pages. One lists two front caliper families – a small round body and a larger half-moon – and jokes you simply lived with what you were delivered. With the small bodies he reports excellent feel and short pad life (10–15k km), to the point of carrying two spare sets and swapping at the first hint of metal. Another recalls a mechanic claiming higher system line pressures than “normal,” which would track with Saab’s insistence on braking as part of its safety brief. Real Car adds the front-wheel parking brake used up to MY1988 and the vented front rotors arriving post-’84—again, year-to-year details matter.

Chassis notes from the video – space-saving spring and damper layout up front, live rear axle with Panhard rod and long arms – show how Saab created room around the engine while giving the rear end predictable kinematics. That feels “kart-like” only when dampers and bushings are fresh; most of the slop people blame on design is tired rubber and wrong tires. Italians who drove them new or nearly new remember stability at speed and calm lane changes with cargo on board. That’s not nostalgia; it’s a function of geometry and mass distribution that was conservative in the right way.

Heat, Intercoolers, and the “Two Cars, Same Series, Different Hardware” Anecdote

One particularly revealing note: two 900 Turbos from the same series delivered to two friends with different under-hood endings – battery and air-to-air intercooler swapped sides, with firewall heat soak on the passenger side in the car where the intercooler sat against the bulkhead. That kind of running-change variance is real in period builds, especially across market codes and supplier batches. It’s also why general statements about “the” 900 tend to fail in comment sections: trim year, target market, and options all matter.

Heat is a recurring theme. The battery near the turbo remains a sore point for some owners; Saab’s foil and shield solution helps, but age and missing pieces turn design compromises into failures. The flip side is a long list of smart heat moves: the location of the ignition module, the airbox and plate behavior under vacuum, and fresh-air flap control via engine vacuum to prevent the cabin from cooking at idle. That integrated thinking is why owners remember AC that actually cooled and cockpits that stayed composed even in Lombardy summers.

Maintenance Truths: What Fails, What Doesn’t, and What You Plan For

Real Car flags ABS pressure accumulators as rare and expensive; Italian owners nod. They accept ordinary wear as normal and report no extraordinary failures across 150,000–200,000 km when the car is maintained like a tool, not a toy. That maintenance plan includes:

- Cooling system integrity as a non-negotiable.

- Transmission respect: clean fluid, mounts, no shock-loading. Abuse, not design alone, is what kills the under-engine gearbox.

- Rust surveillance at drains, arches, scuttle, bonnet and hatch seams, and underbody—especially for Scandinavian imports.

- Glass and trim sourcing planned before you need them. Mechanicals are solvable; interior and glazing can park a car for months.

- Correct pads and rotor spec for your caliper family, not whatever the parts site suggests.

In return, owners cite resale strength even in period. One seller reports +1.5 million lire over his purchase price when he traded to a dealer—evidence that the “nonnina” was already appreciating in the late ’80s when kept straight and clean.

Market and Identity: The Car for People Who Read the Brief

Italian commenters are blunt: the 900 Turbo was not a volume monster at home, but it won morally – and is winning again as values climb. It distinguished you from the “solite tedesche” without giving up robustness. Another adds the cultural stereotype: Saab as the car for architects and engineers, akin to how Lexus reads in certain circles—a quiet signal of a different calculus. That’s not mythology; it’s how product decisions (APC, cockpit ergonomics, safety structure) read to a professional class that valued tools that do work.

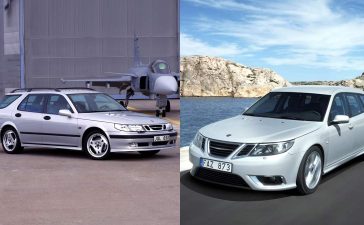

The video’s jab about looks misses that point for many Italians who lived with the car new. They saw originality, aeronautical touches, and a road feel that encouraged tortoise-over-hare progress. They also saw commercial missteps later, when GM-era parts sharing dulled the edge and marketing failed to articulate why Saab’s priorities still mattered. You can love a 900 NG on its own terms, but for many, that’s where the story tilted.

What the Italian Memory Corrects – And What the 900 Still Teaches

Strip the nostalgia and the punchlines, and a clean picture remains. In Italy the 900 Turbo wasn’t a cult curio; it was a professional’s tool with social signal—expensive, yes, but chosen by people who valued cockpit clarity, straight-line stability, and long-day comfort over chrome and theater. The Real Car episode usefully re-centers the engineering (APC logic, packaging, structure), but the comments remind us what that engineering did in the wild: it reduced fatigue, kept high averages without drama, and made owners feel capable rather than merely seen.

The aesthetic argument dissolves under period context. In the mid-’80s, the Saab shape read as aerodynamic intent the same way a 740/760 read as architectural. The 900’s surface language is airflow, cooling, and crash logic—choices that aged better than expected because the car drives the way it looks: calm, planted, and efficient with its effort. Call it beauty by performance audit.

The ownership notes are not romantic; they’re procedural. Keep heat shields, drains, mounts, and coolant in spec; understand your caliper family; respect the under-engine gearbox; plan glass and trim before you need them. Do that, and the supposed “fragilities” shrink to a shortlist of known, budgetable risks. In exchange you get a car that still covers distance at a professional pace, seats that make a six-hour day feel like four, and a turbo system that was designed to save pistons and time, not YouTube thumbnails.

Italian lived experience also corrects the myth of isolation. The 900 Turbo competed for visible buyers –managers, agents, creatives – and, in certain cities, it was part of the street furniture. The market didn’t reject it on looks; it hesitated on price and later lost the thread when GM-era homogenization dulled Saab’s edge. That’s not an indictment of the original 900; it’s a lesson in brand translation: if you don’t explain why your odd choices make life better, someone else will sell a simpler story.

What remains in 2025 is clarity. The 900 Turbo teaches that ergonomics and stability are speed, that service access is product design, and that knock-aware boost is worth more in the real world than brochure peak numbers. It also proves a social point: cars can be status without being loud. Among people who remember its working years, the 900’s reputation isn’t “misunderstood” – it’s earned.

So the Italian verdict stands: set aside the memes, buy on structure and systems, and the 900 Turbo repays you the way good tools do – not with spectacle, but with results.