When Saab introduced the all-new 9-3 Sport Sedan in 2002 for the 2003 model year, most of the attention naturally focused on chassis dynamics, turbocharged drivetrains, and the switch from the OG 9-3’s classic hatchback to a more modern sedan design. What went largely unnoticed outside Sweden was something far more unusual: the new 9-3 quickly became the country’s most difficult car to steal.

That is not a figure of speech. It was a measurable, documented fact. In late 2003, SSF Stöldskyddsföreningen, Sweden’s national theft-prevention authority, published its annual ranking of vehicles based on resistance to both break-ins and full-vehicle thefts. The Saab 9-3 Sport Sedan topped the list, outperforming competitors from Volvo, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Audi, and Volkswagen.

Two independent Swedish publications – Auto Motor & Sport and MotorMagasinet – reported the same conclusion: The 2003 Saab 9-3 Sport Sedan was officially Sweden’s most theft-secure car.

The headlines were short and direct, typical of Swedish journalism:

“Saab 9-3 mest stöldsäkra bilen.”

“Saab 9-3 Sport Sedan mest stöldsäkra bilen.”

Behind these concise titles was a story of engineering decisions Saab had been making for decades, rooted in an aviation mindset where system integrity always comes before convenience. The 9-3 simply made that philosophy impossible to ignore.

A Security Architecture Designed Like an Aircraft System

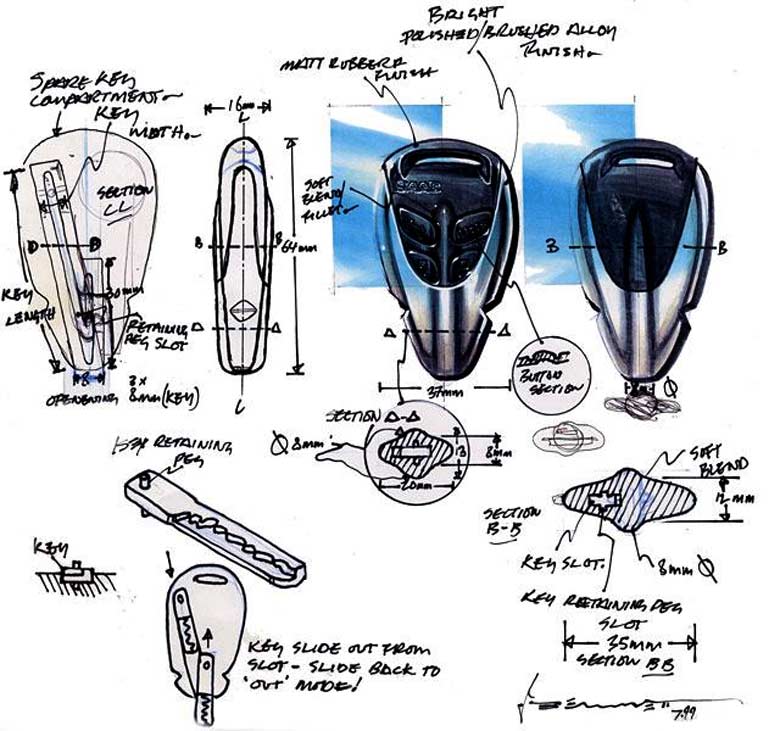

Saab’s theft-protection strategy was never about marketing. It did not rely on gimmicks, blinking LEDs, or aftermarket add-ons. Instead, the company built the new 9-3 with an electronically integrated security ecosystem where each component authenticated the next.

The key, immobilizer, ECU, and steering lock were not separate elements working in parallel – they were interdependent. Remove one, and the others refused to cooperate. Attempting to bypass them required intimate knowledge of Saab’s proprietary coding structure, and even then, you needed access to hardware and cryptographic sequences that simply were not obtainable outside authorized channels.

The logic was straightforward: If anyone wanted to start a 9-3, the car had to agree that they were allowed to start it. This was very unlike many competitors of the era, whose immobilizers could be bypassed with relay attacks, cloned keys, or manipulation of wiring harnesses under the dash. Saab’s system was not invincible – no system is – but for practical, real-world thieves, it was close enough.

SSF’s assessment confirmed precisely that. When thieves targeted Swedish parking lots, Saab 9-3s were left untouched.

The Rare Case of ‘Stolen Saabs’ – Not Really Stolen

Here is the part of the story that enthusiasts find both amusing and telling: Across two decades of production (2003–2014 for the Sport Sedan and Convertible, 2005–2014 for the SportCombi), and countless ownership stories shared in clubs, forums, regional police reports, and insurance archives, there is still no verified case of a Saab 9-3 being stolen without its key.

Every anecdote that surfaces tends to follow the same predictable pattern:

- The owner forgot the key in the car.

- A family member took the car without telling them.

- The key was misplaced and assumed stolen.

- The original key was kept in the glovebox (yes, this happens).

No locksmith override.

No relay attack.

No “laptop-based hacking.”

And importantly – no successful ignition bypass.

This consistency is remarkable when viewed in contrast with what happened across the automotive world during the same period. Many mainstream brands suffered escalating theft rates as criminals learned to manipulate OBD ports, exploit wireless key signals, or bypass immobilizers that relied only on static RFID codes. Saab’s multi-layer system, which required synchronized authentication between several modules, did not surrender to such techniques.

Even today, in an era where videos of thieves stealing cars in 15 seconds circulate across social media, a second-generation Saab 9-3 remains nearly absent from modern theft tutorials.

Thieves simply move on to easier targets.

2003: The Year the Industry Took Notice

The announcement in 2003 by SSF did more than put Saab at the top of a ranking. It highlighted something engineers inside Trollhättan already knew: the new Epsilon-based 9-3 had a security platform that other manufacturers would struggle to match without redesigning their electronic architectures.

The Swedish market understood the significance. Car theft in the early 2000s was still a prominent issue – professional theft rings were common, and insurance companies tracked loss data with extraordinary precision. When a new model entered the market and, within months, was declared the country’s most theft-secure vehicle, it was not taken lightly.

Auto Motor & Sport noted that the 9-3 had risen to the top due to its structural resistance to unauthorized startup. MotorMagasinet went further, pointing out that the effectiveness of the system stemmed from engineering rather than add-ons or accessories.

To put it simply: The 9-3 was not “protected” from theft. It was built not to be stolen.

A Legacy That Continued Without Interruption

What makes the story so unique is that Saab did not dilute or simplify the system over the following decade. Whether a 9-3 was delivered as a 1.8i, an Aero V6, a 1.9 TiD, or the late-life Griffin model, its security philosophy remained the same.

Owners of 2007–2011 models often comment on how even authorized technicians require security access codes and Tech2 authentication procedures to program new keys. The inconvenience is well-known – but the reason is the same system philosophy that earned the 2003 model its award.

Saab never took shortcuts, never downgraded components, and never introduced “cheaper” key variants that compromised security.

As a result, a striking pattern emerged: The theft-protection ranking earned in 2003 effectively carried through the entire production life of the 9-3.

In markets like the UK, Netherlands, Germany, and even the US (where vehicle theft trends differ significantly from Sweden), the 9-3 maintained one of the lowest theft-rates in its class – year after year.

And again, not because Saab advertised it. Because the system worked.

Why Thieves Avoid the 9-3, Even Today

Several factors contribute to the model’s enduring reputation:

- No quick ignition bypass – Hot-wiring is impossible. The entire network of modules must handshake correctly before the engine control unit will allow ignition.

- Highly encrypted keys – Cloning a Saab key requires access to both Saab-specific equipment and security codes that were never leaked – even after the factory closed.

- Tech2 authentication barrier – Any attempt to program or force-pair a key demands authorized access procedures. This alone stops opportunistic thieves.

- Low criminal resale value – Because Saabs are a niche market, a stolen 9-3 is very difficult to resell or dismantle discreetly.

- Strong owner community – Saab enthusiasts track chassis numbers, parts, and local vehicles with near-obsessive accuracy. A suspicious 9-3 does not stay hidden for long.

Together, these factors create a scenario where stealing a 9-3 is not only difficult – it is irrational.

A 22-Year Record That Speaks for Itself

From the moment the 9-3 Sport Sedan debuted in 2003, through the final Griffin editions in 2011–2012, and even a decade beyond production, the model’s theft-resistance story has remained consistent:

No confirmed theft without the key.

No successful ignition bypass.

No working criminal technique.

In a world where car theft has become a high-tech arms race, the Saab 9-3 stands as a curious anomaly – a product of early-2000s engineering that remained future-proof in an area where most brands struggled.

It is one of the few automotive achievements Saab never promoted aggressively, but perhaps should have. The 2003 award in Sweden was more than a footnote; it was the beginning of a security legacy that followed every 9-3 produced after it.

Two decades later, the verdict remains unchanged: A Saab 9-3 disappears only when its owner forgets the key.